FREE Online Event

FREE Online Event

Saturday, March 6, 2021

Online Premiere at 7:30pm

Youthful

Gifts

WATCH THE REBROADCAST

FREE Online Event

FREE Online Event

Saturday, March 6, 2021

Online Premiere at 7:30pm

Youthful Gifts

WATCH THE REBROADCAST

FREE Online Event

FREE Online Event

Saturday, March 6, 2021

Online Premiere at 7:30pm

Youthful

Gifts

WATCH THE REBROADCAST

Time to event

Duration

1 hour

Share With

About this performance:

The young genius, Mendelssohn, precocious on the level of Mozart, composed 12 astonishing symphonies before the age of 14. His string symphony No. 9 shows a mastery of drama, lyricism and humor. The Trio includes the little folk song, La Suisse, yodel included! Coleridge-Taylor, a trailblazer of his time for composers of color was extraordinarily gifted at a young age. The series of graceful movements may be played in any order, and never fail to delight.

Exclusive to Subscribers

Subscribers who have a current subscription to the 2020-2021 Season will be invited to a virtual VIP Green Room Q&A post-concert with Michael Stern and musicians of the Stamford Symphony

Performance by:

Michael Stern, conductor

Program:

Felix Mendelssohn String Symphony No.9 in C Major, La Suisse (1823)

I.Grave – Allegro

II.Andante

III.Scherzo and Trio (La Suisse)

IV.Allegro vivace

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor 4 Novelletten for String Orchestra, Op.52

No.3

No.4

Program Notes:

String Symphony No. 9 in C major, “Swiss”

Felix Mendelssohn

1809-1847

The String Symphony No. 9, composed in March, 1823, is one in a series of twelve that Felix Mendelssohn composed between the ages of 12 and 14. Previously, he had already written a piano trio, a cantata, a violin sonata, four piano sonatas, two operettas and numerous lesser works. He was an accomplished pianist, organist and violinist; in his spare time, he practiced drawing and playwriting with his talented sister Fanny, proving to be a creditable artist. The writer and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who knew Mozart and Mozart personally, said that comparing Mozart’s childhood oeuvre to Mendelssohn’s at the same age like comparing “the prattle of a child” to “the cultivated talk of an adult.”

Mendelssohn received his entire education from carefully selected private tutors; his and Fanny’s counterpoint teacher, Carl Friedrich Zelter was unrelentingly rigorous, and wasted no time on awestruck admiration of his brilliant student. Mendelssohn composed the string symphonies for musical soirées held every Sunday in his parent’s palatial home in Berlin, to which Europe’s most famous intellectuals had a standing invitation. Later, Mendelssohn was embarrassed by, and suppressed, these youthful works, considering them his “apprenticeship.” They remained unpublished until the late 1950s and were first recorded in only in 1971.

Mendelssohn experimented in the String Symphony No. 9, dividing the viola sections in three of the four movements, and dividing the violins in four in the Andante. Zelter drilled his student in fugal counterpoint, and with the exception of the Scherzo, all movements have extensive fugal passages – Zelter probably “corrected” various contrapuntal flaws in its three fugues. We can thank Zelter’s obsession with fugal counterpoint for the Bach renaissance that has lasted to this day: Six years later, Mendelssohn conducted a revival of Bach’s major works with the first public performance of the St. Matthew Passion in Berlin.

The solemn, slow introduction leading into the lively first movement reveals undeniably the influence of Haydn. The agitated accompaniment would become one of Mendelssohn’s musical fingerprints. The second theme is only a slight variation of the first.

In the Andante, sandwiched between the dreamy opening and closing sections, is a four-voiced fugue in the lower strings in the style of Bach, with the divided violins playing in their highest register.

The Symphony derives its title from the Scherzo, titled “La Suisse.” It is modeled after Beethoven, who invented this departure from the Classical minuet. In the trio Mendelssohn inserts one of his rare examples of actual folk music, a genre that, later in life, he claimed to detest. As a memento of his first visit to Switzerland, he quotes a popular yodeling song, complete with drone, nearly the same theme Haydn used for the finale of his Symphony No. 104.

No one has ever doubted Mozart’s uncontrolled, exuberant childishness; the image of the youthful Mendelssohn is more disciplined and staid. Yet, Felix was a teenager too, and his own exaggerated adolescent enthusiasm is evident in the frenetic finale – even more than in the first-movement Allegro. The obligatory fugue whips by as if to avoid Zelter’s critical scrutiny. With Haydn-like humor, it slams on the brakes midway through, only to take off at twice the speed in a mad rush to the finish.

From Four Novelletten, Op. 52

No. 3, Andante espressivo

No. 4,Allegro con brio

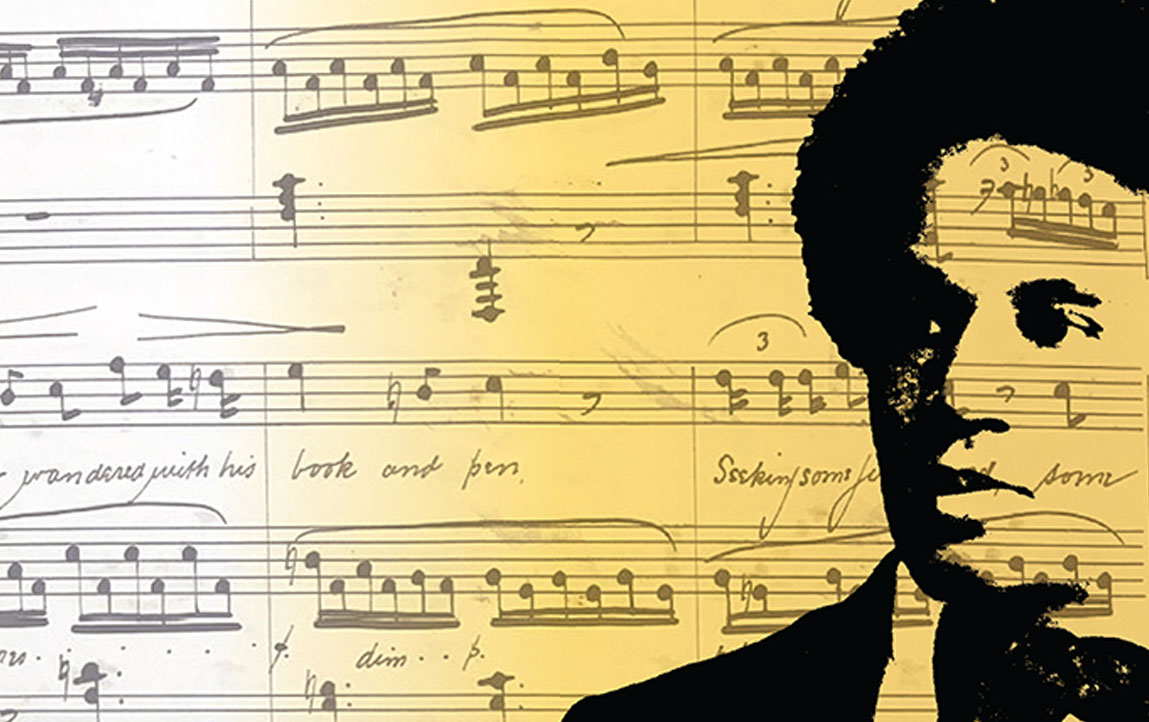

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

1875-1912

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was an English composer, the illegitimate son of a British mother and a father who was a doctor and a native of Sierra Leone. Coleridge-Taylor had a meteoric career, cut short by pneumonia. He entered the Royal College of Music at 15 and had his first music published at 17. In England, his cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, ranked just below Messiah and Elijah in popularity with English choral aficionados early in the twentieth century. He composed two Hiawatha sequels to form a choral trilogy.

Coleridge-Taylor tried to integrate the music of his West African roots into classical music with 2 Moorish Tone-Pictures (1897) and African Suite (1898). He made three trips to the United States at the invitation of the Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society for African American men. After the first of these trips to the United States, he became interested in African American music, composing Four African Dances (1904) and 24 Negro Melodies (1905), transcriptions of spirituals for chamber orchestra.

Coleridge-Taylor was also an excellent and exacting conductor, the permanent conductor of the Handel Society from 1904 until his death. In 1910, New York orchestral players referred to him as the “black Mahler.”

The Novelletten could be called high-quality salon music, a genre popular before World War I, when musical soirees in private homes were all the rage. The term Novellette was coined by Robert Schumann to describe the narrative quality of a musical work. Interestingly, Schumann was creating an elegant pun, bearing on the relationship of the new term to the literary “novel,” and “novelty,” as well as to the name of the English soprano Clara Novello. Coleridge-Taylor extended the punning by publishing the Novelletten with the publisher Novello.

The Novelletten were composed in 1903 for violin and piano and in an alternate version for string orchestra with tambourine and triangle. The unusual addition of tambourine and triangle to the classic string orchestra renders the pieces effectively eclectic and colorful.

Program notes by:

Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

Technical requirements:

You’ll need an internet connection and the ability to stream audio and video to enjoy your experience.

We recommend an internet speed of 50MBPS, and viewing the experience or event on a computer, for an optimal experience.