LIGHT AND LOVE REVEALED

Saturday, November 19 at 7:30pm

LIGHT AND LOVE REVEALED

Saturday, November 19 at 7:30pm

LIGHT AND LOVE REVEALED

Saturday, November 19 at 7:30pm

Location

The Palace Theatre

61 Atlantic Street, Stamford, CT 06901

Duration

2 hours with a 20

minute intermission

Share With

About this performance

Einojuhani Rautavaar’s Into the heart of light bubbles with energy as it creates the illusion of being underwater in the darkness, looking upwards towards a distantly shining light. Beethoven’s Leonore Overture written for his only opera, Fidelio, a profound love story, is inspired by Leonore’s rescue of her wrongly imprisoned husband from his dungeon cell and brings him back into the light. The mystery and touching beauty of Schubert’s miraculous Unfinished Symphony expresses the frailty, vulnerability, and longing of the human condition. World-renowned cellist Alisa Weilerstein plays Dmitri Shostakovich’s formidable first Cello Concerto, one of the most technically demanding and soul-searching works for the cello.

Michael Stern, conductor

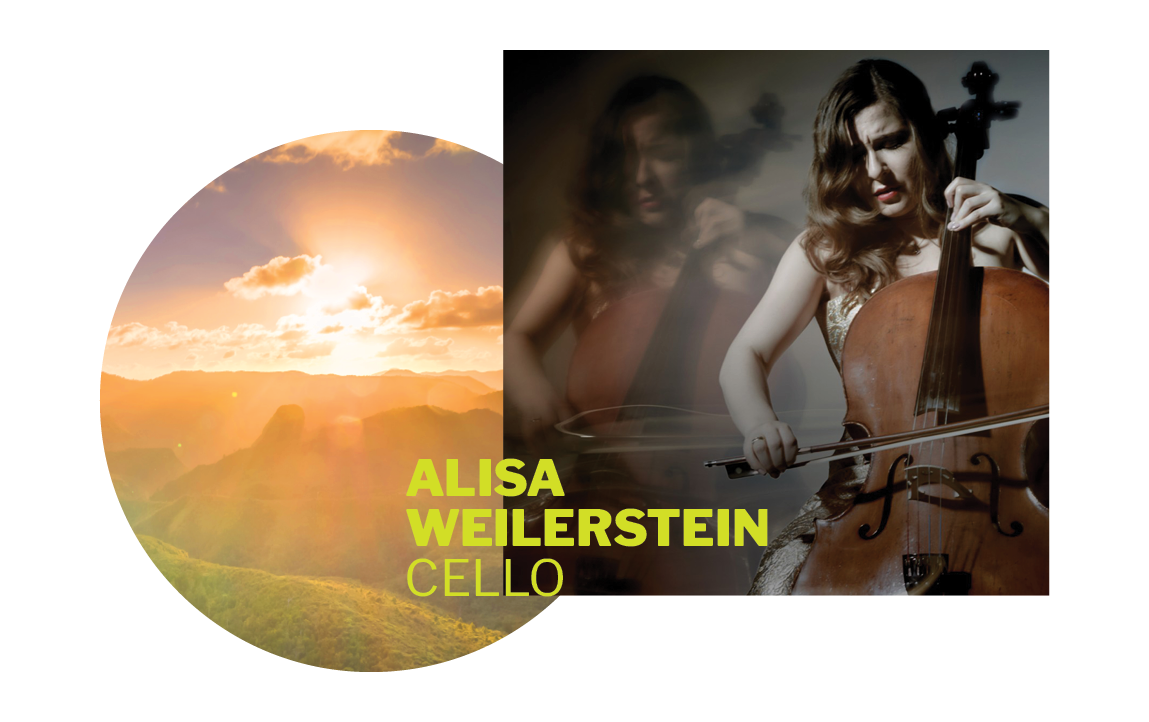

Alisa Weilerstein, cello

Special Event

ALISA WEILERSTEIN AND MICHAEL STERN IN CONVERSATION WITH J.S. BACH

In this special concert Alisa Weilerstein talks to Michael Stern about why Bach continues to remain fundamental to Western classical music. As illustration she will play Bach’s cello suites No. 1 in G BWV 1007 and No. 2. in D minor BWV 1008.

$35 General Admission

Sunday, November 20 at 2:30pm

Behind the Baton

Learn more about the program during this pre-concert talk hosted by Music Director Michael Stern. Behind the Baton begins one hour before each concert at the Palace Theater.

Musical Program to include

Einojuhani Rautavaara Into the heart of light

Dmitri Shostakovich Cello Concerto No. 1

Franz Schubert Symphony No. 7 Unfinished

Ludwig van Beethoven Leonore Overture, No. 3

Featured Artists

Alisa Weilerstein cello

Alisa Weilerstein is one of the foremost cellists of our time. Known for her consummate artistry, emotional investment and rare interpretive depth, she was recognized with a MacArthur “genius grant” Fellowship in 2011. Today her career is truly global in scope, taking her to the most prestigious international venues for solo recitals, chamber concerts, and concerto collaborations with all the preeminent conductors and orchestras worldwide. “Weilerstein is a throwback to an earlier age of classical performers: not content merely to serve as a vessel for the composer’s wishes, she inhabits a piece fully and turns it to her own ends,” marvels the New York Times. “Weilerstein’s cello is her id. She doesn’t give the impression that making music involves will at all. She and the cello seem simply to be one and the same,” agrees the Los Angeles Times. As the UK’s Telegraph put it, “Weilerstein is truly a phenomenon.”

Bach’s six suites for unaccompanied cello figure prominently in Weilerstein’s current programming. Over the past two seasons, she has given rapturously received live accounts of the complete set on three continents, with recitals in New York, Washington DC, Boston, Los Angeles, Berkeley and San Diego; at Aspen and Caramoor; in Tokyo, Osaka, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, London, Manchester, Aldeburgh, Paris and Barcelona; and for a full-capacity audience at Hamburg’s iconic new Elbphilharmonie. During the global pandemic, she has further cemented her status as one of the suites’ leading exponents. Released in April 2020, her Pentatone recording of the complete set became a Billboard bestseller and was named “Album of the Week” by the UK’s Sunday Times. As captured in Vox’s YouTube series, her insights into Bach’s first G-major prelude have been viewed almost 1.5 million times. During the first weeks of the lockdown, she chronicled her developing engagement with the suites on social media, fostering an even closer connection with her online audience by streaming a new movement each day in her innovative #36DaysOfBach project. As the New York Times observed in a dedicated feature, by presenting these more intimate accounts alongside her new studio recording, Weilerstein gave listeners the rare opportunity to learn whether “the pressures of a pandemic [can] change the very sound a musician makes, or help her see a beloved piece in a new way.”

Earlier in the 2019-20 season, as Artistic Partner of the Trondheim Soloists, Weilerstein joined the Norwegian orchestra in London, Munich and Bergen for performances including Haydn’s two cello concertos, as featured on their acclaimed 2018 release, Transfigured Night. She also performed ten more concertos by Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Elgar, Strauss, Shostakovich, Britten, Barber, Bloch, Matthias Pintscher and Thomas Larcher, with the London Symphony Orchestra, Zurich’s Tonhalle Orchestra, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne, Tokyo’s NHK Symphony, the New York Philharmonic, and the Houston, Detroit and San Diego symphonies. In recital, besides making solo Bach appearances, she reunited with her frequent duo partner, Inon Barnatan, for Brahms and Shostakovich at London’s Wigmore Hall, Milan’s Sala Verdi and Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw. To celebrate Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, she and the Israeli pianist performed the composer’s five cello sonatas in Cincinnati and Scottsdale, and joined Guy Braunstein and the Dresden Philharmonic for Beethoven’s Triple Concerto, as heard on the duo’s 2019 Pentatone recording with Stefan Jackiw, Alan Gilbert and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields.

Committed to expanding the cello repertoire, Weilerstein is an ardent champion of new music. She has premiered two important new concertos, giving Pascal Dusapin’s Outscape “the kind of debut most composers can only dream of” (Chicago Tribune) with the co-commissioning Chicago Symphony in 2016 and proving herself “the perfect guide” (Boston Globe) to Matthias Pintscher’s cello concerto un despertar with the co-commissioning Boston Symphony the following year. She has since reprised Dusapin’s concerto with the Stuttgart and Paris Opera Orchestras and Pintscher’s with the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne and with the Danish Radio Symphony and Cincinnati Symphony, both under the composer’s leadership. It was also under Pintscher’s direction that she gave the New York premiere of his Reflections on Narcissus at the New York Philharmonic’s inaugural 2014 Biennial, before reuniting with him to revisit the work at London’s BBC Proms. She has worked extensively with Osvaldo Golijov, who rewrote Azul for cello and orchestra for her New York premiere performance at the opening of the 2007 Mostly Mozart Festival. Since then she has played the work with orchestras around the world, besides frequently programming his Omaramor for solo cello. Grammy nominee Joseph Hallman has written multiple compositions for her, including a cello concerto that she premiered with the St. Petersburg Philharmonic and a trio that she premiered on tour with Barnatan and clarinetist Anthony McGill. At the 2008 Caramoor festival, she premiered Lera Auerbach’s 24 Preludes for Violoncello and Piano with the composer at the keyboard, and the two subsequently reprised the work at the Schleswig-Holstein Festival, Washington’s Kennedy Center and for San Francisco Performances.

Weilerstein’s recent Bach and Transfigured Night recordings expand her already celebrated discography. Earlier releases include the Elgar and Elliott Carter cello concertos with Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin, named “Recording of the Year 2013” by BBC Music, which made her the face of its May 2014 issue. Her next album, on which she played Dvořák’s Cello Concerto with the Czech Philharmonic, topped the U.S. classical chart, and her 2016 recording of Shostakovich’s cello concertos with the Bavarian Radio Symphony and Pablo Heras-Casado proved “powerful and even mesmerizing” (San Francisco Chronicle). She and Barnatan made their duo album debut with sonatas by Chopin and Rachmaninoff in 2015, a year after she released Solo, a compilation of unaccompanied 20th-century cello music that was hailed as an “uncompromising and pertinent portrait of the cello repertoire of our time” (ResMusica, France). Solo’s centerpiece is Kodály’s Sonata for Solo Cello, a signature work that Weilerstein revisits on the soundtrack of If I Stay, a 2014 feature film starring Chloë Grace Moretz in which the cellist makes a cameo appearance as herself.

Weilerstein has appeared with all the major orchestras of the United States, Europe and Asia, collaborating with conductors including Marin Alsop, Daniel Barenboim, Jiří Bělohlávek, Semyon Bychkov, Thomas Dausgaard, Sir Andrew Davis, Gustavo Dudamel, Sir Mark Elder, Alan Gilbert, Giancarlo Guerrero, Bernard Haitink, Pablo Heras-Casado, Marek Janowski, Paavo Järvi, Lorin Maazel, Cristian Măcelaru, Zubin Mehta, Ludovic Morlot, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Peter Oundjian, Rafael Payare, Donald Runnicles, Yuri Temirkanov, Michael Tilson Thomas, Osmo Vänskä, Joshua Weilerstein, Simone Young and David Zinman. In 2009, she was one of four artists invited by Michelle Obama to participate in a widely celebrated and high-profile classical music event at the White House, featuring student workshops hosted by the First Lady and performances in front of an audience that included President Obama and the First Family. A month later, Weilerstein toured Venezuela as soloist with the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra under Dudamel, since when she has made numerous return visits to teach and perform with the orchestra as part of its famed El Sistema music education program.

Born in 1982, Alisa Weilerstein discovered her love for the cello at just two and a half, when she had chicken pox and her grandmother assembled a makeshift set of instruments from cereal boxes to entertain her. Although immediately drawn to the Rice Krispies box cello, Weilerstein soon grew frustrated that it didn’t produce any sound. After persuading her parents to buy her a real cello at the age of four, she developed a natural affinity for the instrument and gave her first public performance six months later. At 13, in 1995, she made her professional concert debut, playing Tchaikovsky’s “Rococo” Variations with the Cleveland Orchestra, and in March 1997 she made her first Carnegie Hall appearance with the New York Youth Symphony. A graduate of the Young Artist Program at the Cleveland Institute of Music, where she studied with Richard Weiss, Weilerstein also holds a degree in history from Columbia University. She was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) at nine years old, and is a staunch advocate for the T1D community, serving as a consultant for the biotechnology company eGenesis and as a Celebrity Advocate for JDRF, the world leader in T1D research. Born into a musical family, she is the daughter of violinist Donald Weilerstein and pianist Vivian Hornik Weilerstein, and the sister of conductor Joshua Weilerstein. She is married to Venezuelan conductor Rafael Payare, with whom she has a young child.

Program Notes

Into the Heart of Light (Canto V)

Einojuhani Rautavaara

1928-2016

Einojuhani Rautavaara is probably the best-known Finnish composer after Jean Sibelius. He studied at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki and – on the recommendation of Sibelius himself, received a Koussevitzky Foundation fellowship to study in the U.S.A., where his teachers were Vincent Persichetti, Roger Sessions and Aaron Copland. When he returned to Finland, he taught at the Sibelius Academy from 1966 until 1991.

Rautavaara composed in most genres. His 12 concertos include one for double bass and one, Cantus Arcticus, a concerto for birds and orchestra that features his recordings of arctic birds. In the course of his career he has experimented with most contemporary musical languages, but even his serial experiments retained a melodic tone. His eight symphonies and nine operas cover subjects from Russian mystic Grigory Rasputin to painter Vincent Van Gogh in the opera Vincent, which describes various events in the life of the painter.

Rautavaara composed Into the Heart of Light for string orchestra in 2011. Its soundscape, especially the brass, recalls that of Sibelius, but less “tuneful.” Its melodic thread is changed subtly with each repetition. It has been described as “creating the illusion of being under water in the darkness, looking upward towards a distantly shining light.” But perhaps a better description is of viewing the spectacular Northern Lights, which regularly flash across Finland’s skies – subtly similar and repetitive, but never the same.

Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107

Dmitry Shostakovich

1906-1975

If ever we needed evidence that art and politics can make for a lethal mix, the life of Dmitry Shostakovich provides it. A son of the Russian Revolution, he started off as a true believer. But in his early twenties he got caught up in the Stalinist nightmare, apparently surviving the purges only because Stalin liked his “politically correct” music for propaganda films.

In January 1936 an article appeared in Pravda severely criticizing Shostakovich’s highly successful new opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtzensk District. Immediately, upon the order of the government, the opera was withdrawn from the stage and performances of all of the composer’s music banned. For the first of many times Shostakovich was cast into Soviet limbo, his music unperformed, his livelihood taken and his very life in jeopardy. In later years he recalled that he was so certain of being arrested that he used to sleep with his suitcase packed near the front door so that if the secret police were to pick him up, they would not disturb the rest of the family.

World War II brought a breather and an upsurge of patriotism, with the horrors of the ’30s temporarily forgotten. But in 1948 came a resurgence of purges, suppression and disappearances, orchestrated by the cultural commissar Andrey Zhdanov, whose decrees permitted only cheerful, uplifting and folksy art. With Stalin’s death in 1953, however, things began to look up; and later in the decade, when Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization program was underway, Shostakovich felt freer to express himself without fear of retribution. Throughout this political roller coaster, he maintained his artistic integrity by continuing to compose “for the drawer.”

Few musicians in the last century inspired more composers to write for them than did cellist and conductor Mstislav “Slava” Rostropovich. A long-time friend of Shostakovich, with whom he frequently performed around the Soviet Union, Rostropovich had long hoped that the composer would write a cello concerto for him. He recalled that when he raised the question of a commission with Shostakovich’s wife, she answered “Slava, if you want Dmitry to write something for you, the only recipe I can give you is this – never ask him or talk to him about it.” True to form, in 1959, the composer surprised his friend with the Cello Concerto in E-flat.

Although the times may have been calmer, the Concerto opens with a grim four-note theme on the cello that dominates the movement and recurs throughout the work. Not only is there the inherent musical tension in the chromatic theme but also in the cello part, which begins in the low register, gradually ratchets higher and higher, transforming the theme into a shriek. The second theme offers less contrast than one might expect in a sonata form, but at least it attenuates the anger; the composer, however, couldn’t resist appending his grim motto.

The lyrical second movement opens with a plaintive theme based on a Jewish folksong. It is one of Shostakovich’s most romantic movements and leads into a huge written-out cadenza that the composer notated as a separate movement. In it, the grim four-note motive from the opening movement reappears, and the tempo slowly increases until the cadenza transitions into the Allegro finale.

It is characteristic of many of the finales of Shostakovich’s symphonies and concertos to have a playful and often satiric bite. Stalin may have been dead and even discredited, but Shostakovich could not let him off that easily. Hidden in the last movement is a parody of one of the dictator’s favorite sentimental ditties, Suliko, the same one the composer parodied in the satirical cantata Rayok (The Peep Show), lampooning Zhdanov’s and his followers’ decrees. The cantata, probably composed in stages between 1947 and 1967, remained hidden “in the drawer” until after the composer’s death. Shostakovich also brings back and prominently features the four-note motto, concluding with a reprise of the opening of the Concerto. If there is any personal or political significance or symbolism associated with it, none has been determined with any certainty.

Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D. 759

“The Unfinished”

Franz Schubert

1797-1828

Franz Schubert had “burned out” and abandoned teaching after two years in his father’s school, joining instead nineteenth-century Vienna’s “hippie” subculture. His hangouts were cafés, beer halls and dance halls, and he never held a steady job except for occasional private teaching. Luckily, his better-heeled friends were generous with funds, and he repaid them with his Lieder – often scribbled on napkins and scraps of paper – and informal performances, nicknamed Schubertiaden. These evenings, with Schubert playing his music surrounded by colleagues and friends, were popular – if unremunerative – entertainment in Vienna. One of the tragic consequences of this lifestyle was the syphilis which was diagnosed in 1822 and which would kill him six years later.

That same year, the Styrian Music Society in Graz presented Schubert a Diploma of Honor, which the composer acknowledged with the gift of the symphonic fragment to its representative and his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner, a minor composer. Hüttenbrenner, however, did not disclose its existence until 1865 when he used it as bait to get one of his own compositions performed. The mystery that surrounds its composition and subsequent fate has probably elicited more conjecture and learned papers than any other symphonic work.

Schubert is notorious for leaving behind unfinished manuscripts. We still do not know, and probably never will, why Schubert never completed the symphony. He had already composed six symphonies, but these were relatively youthful products, the latest composed in 1818. The incomplete autograph manuscript also includes a fragment of a third (Scherzo) movement. At the time he was composing this symphony, Schubert was in awe of Beethoven, especially his Fifth Symphony, and harbored an almost naïve desire to emulate him. Perhaps he felt that he was unable to live up to such lofty standards. The Scherzo ends abruptly after only 20 measures, followed by a number of blank lined pages. Schubert’s piano draft of this movement has also survived and ends only a few bars later, in the middle of the trio.

Despite the Symphony’s most famous theme – the second melody in the first movement – the first movement leaves an overwhelming atmosphere of melancholy. It opens with a brief, barely audible introduction in the basses that returns to conclude the movement. The Allegro that follows begins as a sighing motive that ratchets up the tension with its pounding timpani and climbing sequences. Then comes the “famous tune” like a ray of sunshine. The problem is that for the bulk of this long movement Schubert pretty much ignores it, choosing instead to focus on the gloom.

Slow movements of Classical works are usually constructed in ABA form, consisting of a principal melody (A) and a contrasting middle (B) section, often based on the theme. The second movement opens in a more promising mood with a lovely cantabile melody in the upper strings. But in the B section there ensues an emotional battle: a mournful clarinet solo recasts the theme, immediately followed by the oboe in the major mode; but this is interrupted by an angry, despairing orchestral outburst. Schubert frequently employs shifts between major and minor to create abrupt musical mood swings. The fact that he takes the opportunity to repeat the two contrasting sections enhances the emotional tension, which is only released in the final bars of the movement.

Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b

Ludwig Van Beethoven

1770-1827

Beethoven was a perfectionist. He made numerous major revisions to his only opera, Fidelio, before he arrived at the final version we know today. The overture to the opera underwent even greater transformations. The composer wrote four different overtures, all quite different from each other and all still popular in the concert hall. The first three are called Leonore Nos. 1, 2 and 3 respectively, after the name of the heroine of the opera and originally the opera’s title; the fourth is known as Fidelio, the pseudonym she adopts when disguised as a young man.

Leonore, a brave and faithful wife – hence her adopted name – saves her husband, Florestan, from his unjust incarceration by his villainous and powerful enemy Pizzaro. Disguised as Fidelio, she enters into the service of Florestan’s jailer to be nearer her husband. In the end, she manages to liberate not only Florestan, but a whole band of political prisoners when the prison is inspected by the Minister, who has heard rumors of the illegal incarcerations.

Beethoven’s difficulties with the three Leonore overtures stemmed from the fact that they were too dramatically and musically explicit, thus giving away the most exciting moments of the opera, including the appearance of the Minister.

Beethoven composed Leonore No. 3 in 1806 for an abridged performance of the second version of the opera but realized at once how inappropriate it was. It became an independent orchestral composition with one of the most dramatic trumpet calls heralding the Minister’s arrival – and, of course, revealing the denouement before the action even starts.

Program notes by:

Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com

*artists and programs subject to change